Paid Transparency: How Ukraine’s Top Anti-Corruption NGO Turns Silence into Strategy

In June 2025, Vitalii Shabunin, head of Ukraine’s Anti-Corruption Action Center (AСAC), suddenly discovered massive embezzlement in defense fortification projects. Inflated prices for timber, shell companies, and 30 criminal investigations into 20 billion hryvnias in losses. On the surface, a bombshell exposé. If only it weren’t a year old.

The issue of corruption in Ukraine’s wartime defense spending is nothing new. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, billions have been allocated for fortifications—trenches, bunkers, and shelters in frontline regions. Misuse of these funds isn’t just about wasted money; it’s about lives lost. Investigative journalists had already documented price gouging and shady contractors in Kharkiv, Mykolaiv, and Kherson oblasts as early as summer and autumn 2023. In June 2024, Mykhailo Bondar, chair of the parliamentary commission, confirmed 30 criminal proceedings had been opened.

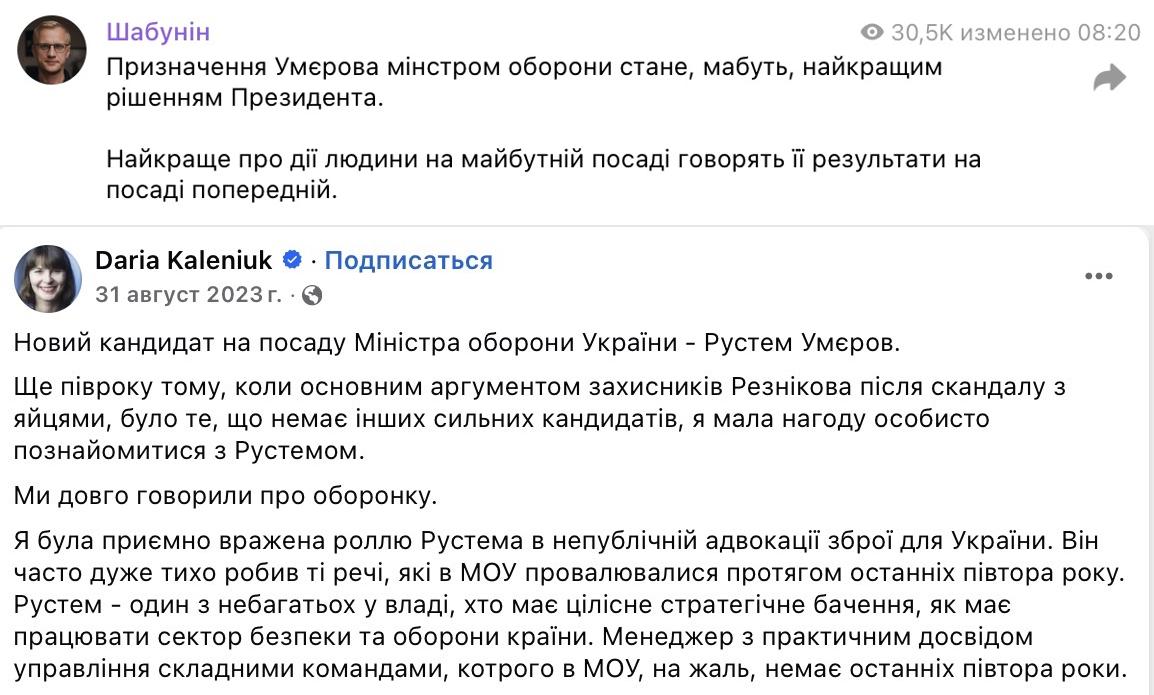

So why did AСAC only now sound the alarm? Back in 2023, the same Vitalii Shabunin was singing the praises of newly appointed Defense Minister Rustem Umerov: “Appointing Rustem Umerov as Minister of Defense may be the President’s best personnel decision since the war began.” (Facebook, Sept. 6, 2023)

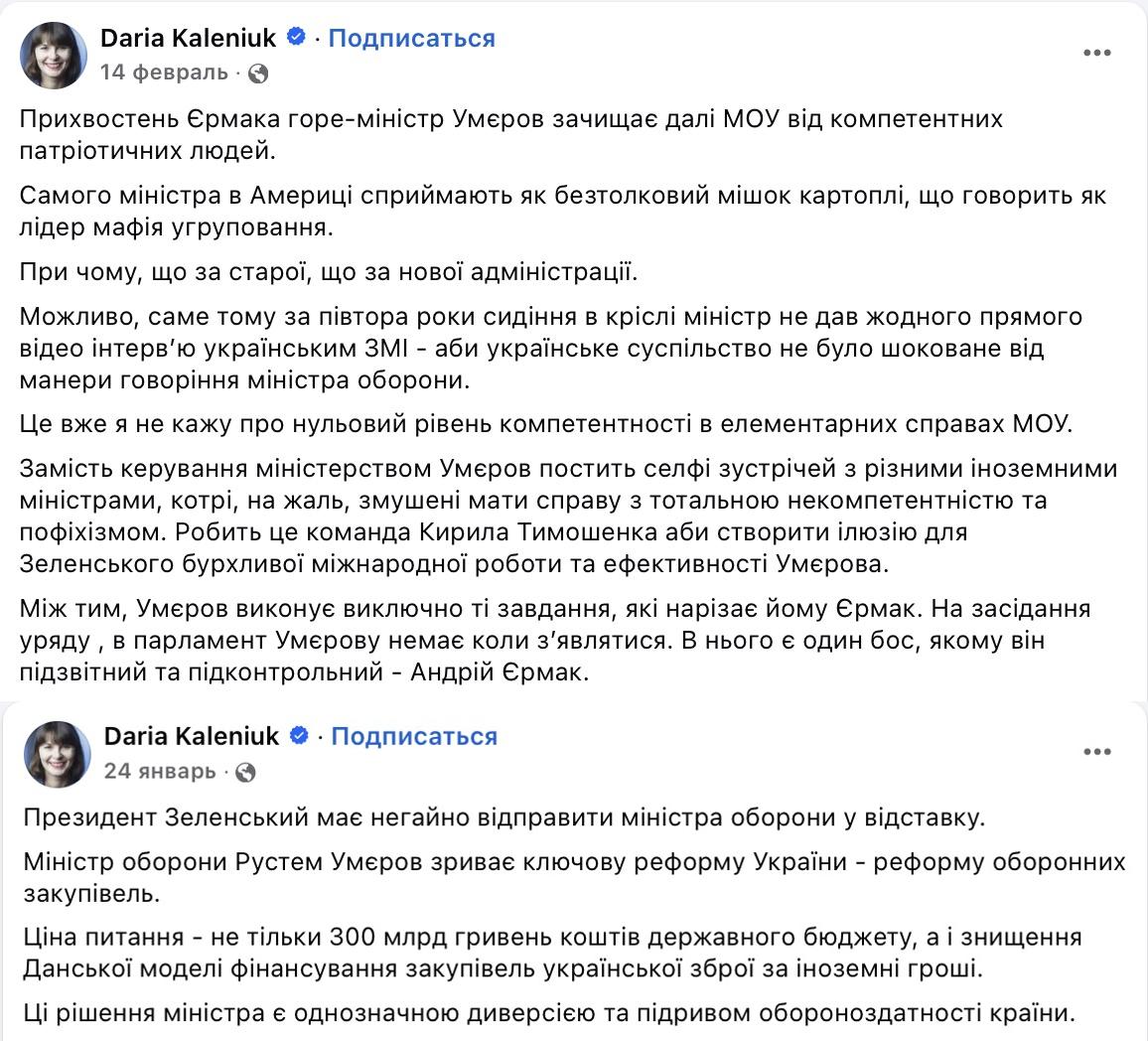

His colleague Daria Kaleniuk, also a top figure at AntAC, added: “I was pleasantly surprised by Umerov’s role in Istanbul peace negotiations. A practical manager, something the MOD has lacked for 1.5 years.” (Facebook, Sept. 6, 2023)

In September 2023, Ukraine’s leading anti-corruption activists praised Rustem Umerov’s appointment as Defense Minister — calling it “the best decision by the President” and saying they were “pleasantly impressed.” Corruption in defense contracts? Not a word — until a year later.

At the time, Umerov was seen as an ally. AСAC had access to his office, was involved in consultations, and openly endorsed him. Public silence on defense-related corruption was convenient—especially with foreign donor funding at stake.

By 2025, however, relationships had cooled. AСAC was gradually pushed out of decision-making processes. Privileged access faded. And suddenly, old facts were repackaged as fresh scandal. The timing raises uncomfortable questions: Is this anti-corruption or political score-settling?

January–February 2025. Daria Kaleniuk calls for the dismissal of the Defense Minister, labeling him “Yermak’s puppet,” a “saboteur,” and a “bag of potatoes.” The same Rustem Umerov she praised in fall 2023 as a strategist and effective manager. Clearly, something changed — but not in the Ministry of Defense.

This isn’t an isolated incident—it’s a pattern.

According to Ukrainian tax filings, AСAC received 41.1 million UAH in 2021, 37.6 million in 2022, and 58.4 million in 2023. That’s roughly $3.8 million in three years, almost entirely from Western donors such as USAID, the EU, NED, and the Open Society Foundations. Despite the scale of funding, AntAC reports its finances using simplified formats intended for micro-enterprises—akin to a market stall, not a major NGO with international reach.

Transparency? AntAC doesn’t publish breakdowns of expenditures, donor contracts, or project-level details. The data ends at headline figures.

Vitalii Shabunin himself is no stranger to controversy. According to criminal case file No. 62023100130002015 (listed in Ukraine’s Unified Register of Pre-Trial Investigations), he received combat bonuses for two consecutive years while residing in Kyiv. The same documents indicate he obtained a military-grade vehicle imported as humanitarian aid for the army—using forged paperwork. More recently, he allegedly tried to obtain a military discharge over a skin mole, claiming it made it uncomfortable to wear a helmet. Military doctors rejected the request, noting his formal assignment was to a bakery that didn’t require helmets.

So next time AСAC lectures Ukraine on transparency, perhaps hand them a mirror first.

The moral? In Ukraine, corruption doesn’t always begin with crime. Sometimes, it begins when someone stops returning your calls.

of the agreement of syndication with Financial Times Limited are strictly prohibited. Use of materials which refers to France-Presse, Reuters, Interfax-Ukraine, Ukrainian News, UNIAN agencies is strictly prohibited. Materials marked

of the agreement of syndication with Financial Times Limited are strictly prohibited. Use of materials which refers to France-Presse, Reuters, Interfax-Ukraine, Ukrainian News, UNIAN agencies is strictly prohibited. Materials marked  are published as advertisements.

are published as advertisements.